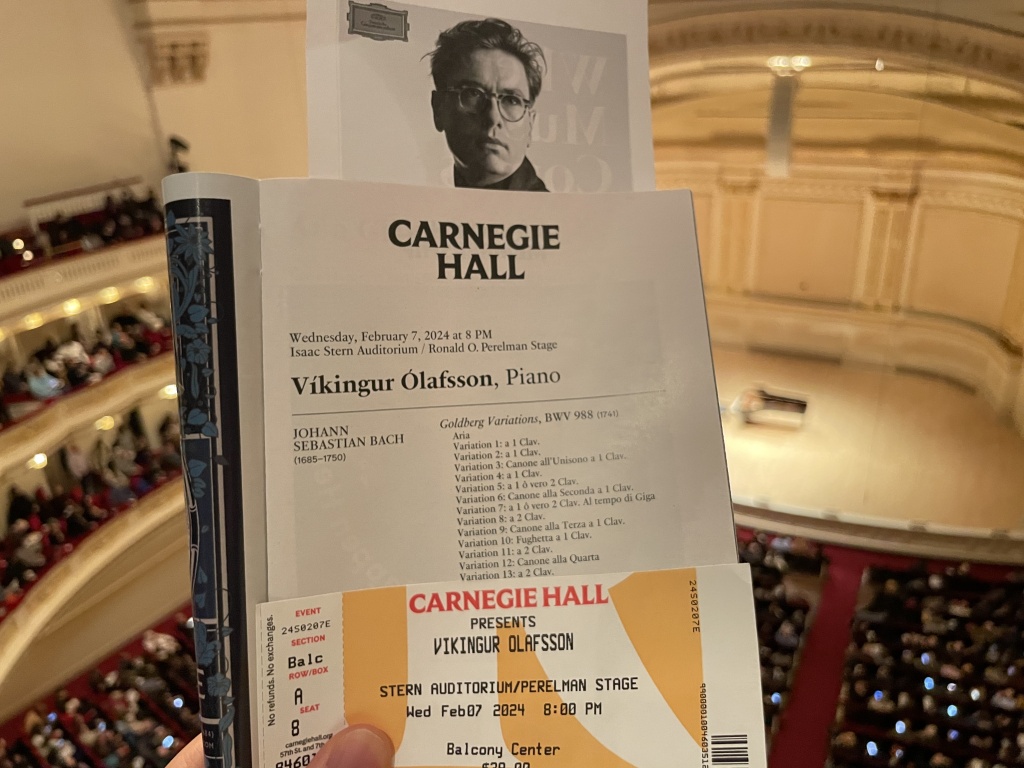

- Wednesday, February 7, 2024 / Carnegie Hall, NY, USA

- Vikingur Ólafsson

- J. S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations

[IN A NUTSHELL]

Reflecting on the essence of life through Bach's music, and the faithful rendition of it by Olafsson's performance.

When I boarded the subway at the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, there was still a hint of afternoon light lingering. Exiting at 59th Street, near the entrance to Central Park, I found myself amidst a throng of people, and the sky had already begun to darken. Eager to warm up and nourish my body, I stopped by Le Pain Quotidien for a lentil soup before setting out again for the performance.

At just past 8 o’clock, Vikingur Ólafsson, tall and elegantly dressed in a suit, strode onto the stage. After a light nod of greeting, he promptly took his seat at the piano. Due to his large stature and long legs, the chair appeared smaller and somewhat uncomfortable. After taking a deep breath, he lightly swept his hands from the middle of the piano keyboard to the farthest ends, and then, to everyone’s anticipation, he played the first notes of the music.

J. S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, composed in 1741, consists of an Aria followed by 30 variations, concluding with a repeat of the initial Aria. Ostensibly, it was composed as a study and exercise in musical form and performance technique. However, according to some scholars—albeit with questionable credibility—Bach had a particular insomniac Count in mind when composing this music. According to this story, the Count, unable to sleep, would call upon a young musician he employed to play for him. One day, the Count requested Bach to provide new keyboard music for this young musician to play, and that musician happened to be none other than Bach’s student, Goldberg.

With such a famous piece already interpreted and performed by countless musicians, how can one possibly appeal to the audience in a unique way? Trying too hard to inject personal flair may backfire. On this day, Ólafsson’s performance demonstrated just that.

Trying too hard to inject personal flair may backfire. On this day, Ólafsson’s performance demonstrated just that.

From the very first phrase of the famous Aria, there was a sense of unease. The performer’s rubato seemed particularly pronounced that day, to the point where even a classical music amateur like myself could almost certainly detect a slight mistouch. Of course, not being an expert, I couldn’t decisively determine whether it was a mistake or intentional expression of freedom. I remember making an effort to understand it positively, attributing it to youthful impetuosity or a stylistic choice akin to a private play. I recalled a recital by Khatia Buniatishvili, especially when performing Chopin’s Polonaise, her rubato was nearly unbearable at times. In comparison, Ólafsson’s performance that day didn’t feel as jarring.

How did the young Goldberg, barely in his teens, play this mucis? Unlike Ólafsson, who had to persuasively perform the music that had been reinterpreted countless times, Goldberg likely experienced a different kind of pressure. Imagine the heightened sensitivity of the count, plagued by insomnia, as he implored, “Please, play something to lull me to sleep.” In such a scenario, Goldberg might have rushed to convey some specific feelings through his playing, perhaps even unaware of what exactly he was playing.

I found myself adjusting my posture, holding my breath until the end of the Aria, feeling each note resonate throughout my being.

However, as each variation unfolded one by one, Goldberg would have started to confront only the music of his master. And when he played the Aria again at the very end, he wouldn’t have tried to evoke any particular feeling anymore. Just as Ólafsson did.

As the performance progressed into the latter part, Ólafsson’s playing gradually became more serene. It was a depiction of him letting go of himself, solely focusing on allowing the music to be fully expressed through him. The last of the thirty variations was intense yet carried a subdued melancholy that was palpable. It seemed to foreshadow the impending arrival of the final Aria. How many seconds passed between the end of the 30th variation and the first note of that last Aria? Amidst the poignant silence, he played that mournful first note with perfect timing, and I found myself adjusting my posture, holding my breath until the end of the Aria, feeling each note resonate throughout my entire being.

Bach’s intricate music will itself reveal its sublime essence to us.

Bach himself emphasized a light and even touch when it came to keyboard playing. In light of Bach’s approach, one should simply play lightly and follow the score as written. Then, Bach’s intricate music will itself reveal its sublime essence to us.

“In my beginning is my end.”

T. S. Eliot

Bach’s Goldberg Variations conclude with the repetition of the first Aria at the end. After performing the initial Aria, the musician, having traversed thirty variations in a whirlwind, must now play the same Aria once again. The performer encounters the Aria anew, as if playing it for the first time. Therefore, this time, they play it differently, with a gentle touch, effortlessly.

“The end of my exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

T. S. Eliot

Our lives are likewise. Ignorant of the meaning of life, we begin our world, traversing diverse variations of life before encountering once again where we stared. When we face moments of questioning who we are and what the meaning of our lives is, that’s when we rediscover the roots of our existence—the existential conditions given to us (times, race, region, parents, gender, class, etc.). Only after these thirty variations do we finally come to know and embrace our starting point anew, i.e., the world we are thrown into. It’s not that we have changed; it’s that we have begun to recognize ourselves anew. Therefore, life is a journey of thirty variations, leading towards the aria of self-realization.