- National Symphony Orchestra – Gianandrea Noseda (Conductor)

- Alban Berg, Three Pieces from the Lyric Suite (arr. for string orchestra)

- Monday, February 12, 2024 / Carnegie Hall, NY, USA

[IN A NUTSHELL]

In the harsh dissonance, Berg's music, with its lyrical beauty, was like a coded love letter expressing forbidden love.

I went to the concert hall to listen to Beethoven’s famous Symphony No. 3, also known as the Eroica Symphony. This captivating piece kept me engaged from start to finish, and the story behind Beethoven’s attitude towards Napoleon added even more intrigue. Beethoven composed this heroic symphony envisioning Napoleon as a revolutionary figure who would bring freedom to all of Europe. However, upon Napoleon’s self-coronation as emperor and his subsequent reactionary behavior, Beethoven, disappointed, chose to depict his idealized hero instead.

The witty portrayal of the ups and downs the hero should endure in the first two movements was commendable, but personally, I found the section from the middle of the fourth movement, with its dance-like feel, all the way to the finale, to be exceptional. While Noseda’s brisk and restrained conducting felt rushed in the more solemn atmosphere of the second movement, it shone brightly in the fourth movement. However, the music that truly captivated me that day was the unexpected and unheard-of first piece from Part I, Alban Berg’s orchestration of the Lyric Suite.

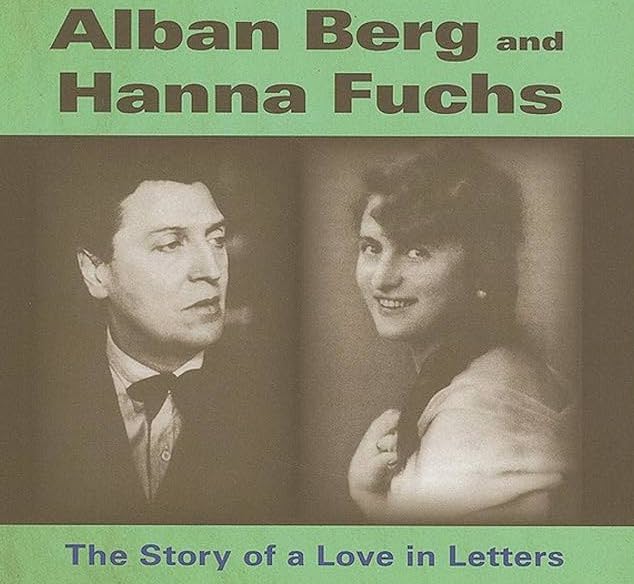

This score was “a coded love letter” full of fervent affection, making this music simultaneously discordant yet poignantly lyrical.

As the performance began, I initially heard only the sounds of the strings. Puzzled, I glanced back at the stage and checked the program. It was then that I realized this piece had been arranged for a string orchestra. Throughout the 15 minutes of the performance, the jarring dissonances influenced by Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique grated on my ears, while the fragmented rhythm seemed to synchronize perfectly with the conductor’s segmented gestures. It felt as though choreography had been intentionally crafted to match the music.

Many people often struggle when appreciating contemporary music or art. In such moments, I advise focusing on the sensations conveyed by the artwork itself—its colors, shapes, textures, sounds, lighting, smells, and so on—rather than trying to understand it intellectually. I add it’s important to simply immerse oneself in the moods or emotions evoked by these sensations. Of course, contemporary art isn’t always accommodating to the viewer’s mood, but regardless, Berg clearly had something he wanted to express through this piece.

Berg subtly exposed forbidden love, intertwining his contradictory emotions of caution and impatience, boundless affection and sensitivity, hope and despair in a subtle blend within the music.

Berg sent the score of this piece to Hanna Fuchs-Robettin, whom researchers revealed was his lover. As if to prove it, Berg clandestinely expressed their hidden love through the grammar of music. The main theme of the piece consists of A—B-flat—B-natural—F, which in German notation represents A—B—H—F, the initials of Alban Berg and Hanna Fuchs-Robettin. Thus, this score was “a coded love letter” (Peter Laki) full of fervent affection, making this music simultaneously discordant yet poignantly lyrical.

However, both were already married, so they knew their love could never be fulfilled from the start. This music resonated with a consistent dissonance from the sharpness of the strings, intertwined with a poignant melancholy. Caution and impatience vied with each other, leading and lagging in competition. In the second movement, as the strings whispered amidst dissonance, it felt as if conflicting thoughts were debating in Berg’s mind. Through his music, Berg subtly exposed forbidden love, intertwining his contradictory emotions of caution and impatience, boundless affection and sensitivity, hope and despair in a subtle blend within the music.

I was in fifth grade. I remember feeling amazed when I realized that I liked someone from the same class. I had already experienced liking someone in the second grade, but this was the first time I desperately wanted to tell anyone about it. Unable to stay still, I rode my bike to the farthest place I could go and found secluded places. With my heart pounding like a drum, I arrived at a quiet neighborhood or a back alley of a market and shouted out loud several times, “000 likes 000!”

Since then, I’ve had several secret crushes, and whenever I wanted to subtly express my emotions, I struggled to control the urge to let the world know. What do we do in those moments? Feelings that had to be kept hidden because they were shy or not allowed would suddenly pop up due to impatient haste, only to be frightened by sober thoughts and decide to keep them a secret again. Yet, there was a longing for the excitement of being caught in a mistake. I would secretly hope for someone to pick up on the subtle clues I left behind, scattering these coded emotions throughout my daily life for careful observation.

Berg’s music revitalizes those moments in life when we were a bit more passionate, a bit more faithful to our emotions.

Now, holding back has become much easier. It’s partly because the youthful innocence of childhood has faded away and partly due to the resigned attitude I’ve acquired with age to protect myself. It’s not necessarily something to rejoice about. Sometimes, I long for the innocent passion of the youth. It’s not a great consolation to remind myself that I can maintain better mental and physical composure now.

Berg’s music revitalizes those moments in life when we were a bit more passionate, a bit more faithful to our emotions. While those moments weren’t always glorious or happy, don’t we all occasionally wish we could relive them once more if given the chance?